Leadership and Deep Change: The Business Case for Organizational Virtuousness

By Brad Winn

We live in a time when it is easy to feel overwhelmed by the relentless pace of change, the revolution in business models, and the complexity of global, national, and social dynamics that challenge the very nature of long-term planning. Some leaders respond only by working harder and asking their colleagues to do the same. Many however are discovering that for them to lead better, they actually have to live better.”1 The idea of living better to lead better assumes a change in the way we are living. That said, some of us as leaders may be more comfortable changing others than ourselves.This installment of Linking Theory + Practice focuses on positive change and the effects of organizational virtuousness on business performance. We look at how leading from a foundation of character and creating a culture of organizational virtuousness may influence business results. The research findings offer a new strategy for living better and leading better.

Positive Change

Throughout history, the most admired leaders have been able to inspire meaningful change in individuals, teams, organizations, and even societies. Yet mastering the art of transformational change is, in fact, one of the most difficult challenges leaders face. Unfortunately many attempts to implement lasting change fail.

Fundamental transformation is what we refer to as “deep change.” Organizational change expert Robert E. Quinn proposes that as the world around us evolves, we have two choices: deep change or slow death. In his book Deep Change: Discovering the Leader Within2, Quinn suggests we are living with constant change in our environment and within our organizations. We respond by choosing one of two behaviors: the choice towards slow death or the choice towards deep change.

“The person who ignores diabetes unknowingly deteriorates until something goes terribly wrong. The person who does not maintain professional skills eventually experiences professional failure. The corporation that ignores market trends and new customer requirements eventually dissolves. One cannot ignore change.”3 The only way to effectively respond to external change is with internal change. “When internal [what the organization is like] and external [what the world is like] alignment is lost, the organization faces a choice: either adapt or take the road to slow death.”4

To illustrate, Quinn tells of a time when he was consulting with a top management team of a large company filled with bright, sincere, and hardworking leaders. The executives were excited to roll out a new strategy that would require change throughout the organization. They anticipated this would improve quality, morale, productivity, and profit. In the midst of their enthusiasm, Quinn told them of a different company in a similar situation whose strategic planning effort, three years later, was deemed a miserable failure. The executives waited anxiously for Quinn’s explanation but instead he asked them why they thought the plan failed.

Quinn then tells what happened next. “A long, heavy silence fell in the room. Finally, one of the most influential members of the group said, ‘The leaders of the company didn’t change their behavior.’ I nodded and pointed out that they themselves had made a lot of assumptions about the behavior that was going to change in others. Now I challenged them: Identify one time when you said that you were going to change your behavior. Again, there was a long pause. Something important and unusual was happening. The members of this group were suddenly seeing that few people ever clearly see—the incongruity of asking for change in others while failing to exhibit the same level of commitment in themselves.”4

One of the most effective ways to lead others to new heights and transform our organizations is to model the necessary changes in ourselves. As M.K. Ghandi wisely stated, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.”

Yet as leaders and as human beings we are sometimes naturally defensive when confronted with a need to change ourselves, especially when challenged with a need for a change that goes to the heart of who we are—our character.

“To thwart our defense mechanisms and bypass slow death, we must confront first our own hypocrisy and cowardice. We must recognize the lies we have been telling ourselves. We must acknowledge our own weakness, greed, insensitivity, and lack of vision and courage. If we do so, we begin to understand the clear need for a course correction, and we slowly begin to reinvent our self. In the end, one of the most powerful ways to change others is to begin with the difficult work of changing ourselves at a deeper level and model the way.

“When we experience failure, it is natural to externalize the problem—to blame some factor that was outside our control. Once in a while this actually does happen. But I have seldom heard anyone say, ‘The change didn’t happen because I failed to model the change process for everyone. I failed to reinvent myself. It was a failure of courage on my part.’ One key to successful leadership is continuous personal change. Personal change is a reflection of our inner growth and empowerment. Empowered leaders are the only ones who can induce real change.”4

Living Better to Lead Better

Living better can take on many aspects of both personal and professional focus. I recently interviewed Eric Severson, former co-CHRO of The Gap and current Chief People Officer at DaVita Kidney Care. He shared part of his journey toward development and balance. “I’ve decided that no matter what hits me at work or in life, in order for me to be my best I have to tenaciously carve out time each day for four wellbeing priorities. Of course, these are not novel ideas, but my prioritization and commitment to these fundamentals are new. First, I now believe that almost everyone including myself needs at least seven hours of sleep. It just has to happen for long-term effectiveness. Second, what we all know from science is that ‘we are what we eat’ so, of course, nutrition is a no-brainer. Third is what I call ‘movement.’ As humans we’re not made to just sit. Fourth is meditation and mindfulness. With regard to prioritization, I have force-ranked them as follows: sleep, eat, move, meditate. If there is insufficient time in any given day, meditation falls off first, followed by movement, eating, and sleeping.”5

Leading better does indeed start with living better and as Severson points out, there are many ways to live a more balanced life, including having the courage to be more conscious of our life choices and developing ourselves, our priorities, and our life choices. This includes taking regular time to be mindful of opportunities to improve not only our professional prowess, but also the goodness of our lives in general.

Character Strengths and Virtues

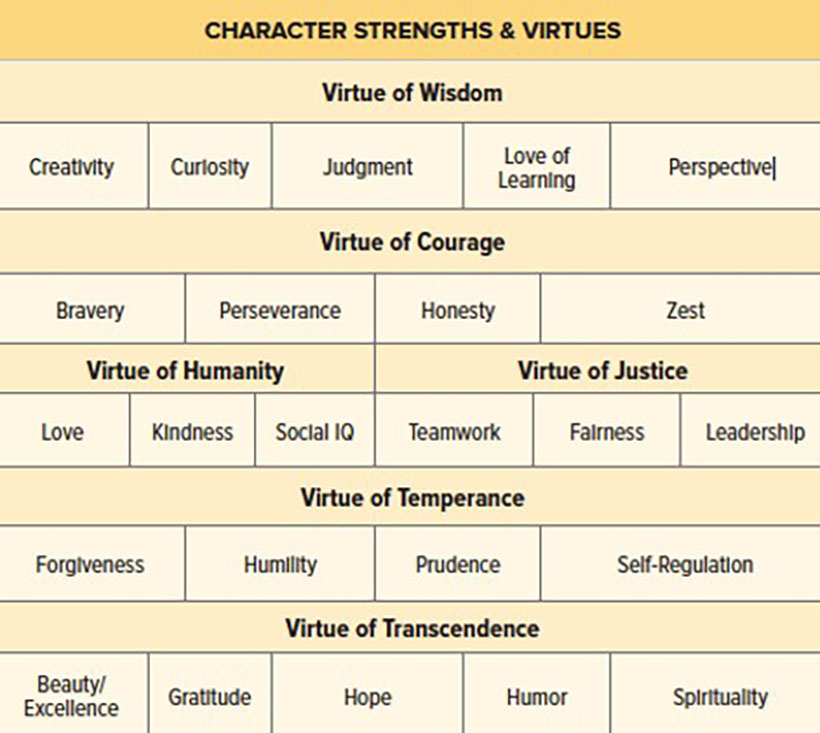

Positive change begins with mindfulness, introspection, and awareness of one’s identity and character. Peterson and Seligman offer insights into possible areas for deep change in their landmark research on classifying character strengths and virtues (see table).6

Bright, Winn, and Kanov (2014) provide a historical foundation for consideration of the virtues in positive social sciences and virtue ethics: “Ideas about virtue have been around for millennia. Since ancient Greek civilization, philosophers have consistently sought to describe conditions that enable thriving for people and society. Writings in the ethics literature about virtue originated in the classical era; Aristotle is one of the earliest thinkers to articulate a theory of virtue. The Greek word for excellence was arete, which was later translated into Latin as virtus. Arete entailed the proper development of character and one’s inner state as a prerequisite for reaching one’s full potential. Aristotle’s virtue is related to the Greek notion of eudaimonia or ‘human flourishing or achieving one’s full potential.’ In Greek society, it was assumed that virtue was essential for experiencing a state of eudaimonia. As the notion of virtue evolved, it came to more specifically connote particular forms of excellence, namely moral and intellectual excellence, signifying the highest good that a human could attain and was linked to the good society. In essence, virtue is about living as a moral and honorable being, and one who is virtuous strives to cultivate such a state. Nearly all accounts of virtue include references to specific virtues like integrity, courage, justice, forgiveness, and compassion among others. Though the specific virtues may vary by context, the idea of virtue as an orientation toward excellence and flourishing seems to be remarkably consistent across time and cultures.”7

Making a positive transformation in our own character provides a moral authority foundation upon which leaders can powerfully stand to inspire others, teams, and organizations to begin the journey toward meaningful and lasting change.

Organizational Virtuousness and Performance

According to their research article entitled “Virtuousness in Organizations,”8 in the Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship, Cameron and Winn state that “an extensive amount of evidence has been produced showing that virtues in individuals are associated with desirable outcomes. For example, honesty, transcendent meaning, caring and giving behavior, gratitude, hope, empathy, love, and forgiveness, among other virtues, have been found to predict desired outcomes, such as an individual’s commitment, satisfaction, motivation, positive emotions, effort, physical health, and psychological health…. That said, few leaders invest in practices or processes that do not produce higher returns to shareholders, profitability, productivity, and customer satisfaction. Without visible payoff, in other words, those with stewardship for organizational resources ignore virtuousness and consider it of little relevance to important stakeholders. Hence, if associations between virtuousness and desired outcomes were to be observed in organizations, evidence of pragmatic utility would be of value. This has been the motive for investigating the relationships between virtuousness and perfor-mance in organizations. A few studies have explored these relationships, and the key results of those investigations are summarized in this section.”

One study investigated eight independent business units randomly selected within a large corporation in the transportation industry. Organizational virtuousness scores for each business unit were measured by survey items measuring compassion, integrity, forgiveness, trust, and optimism. Organizational performance outcomes consisted of objective measures of productivity (efficiency ratios), quality (customer claims), and employee commitment (voluntary turnover) from company records, as well as employee ratings of productivity, quality, profitability, customer retention, and compensation.Organizations with higher virtuousness scores had significantly higher productivity, quality outputs, profit-ability, productivity, customer retention, and lower employee turnover.9

Another investigation of a larger sample of organizations was conducted across 16 industries (e.g., retail, automotive, consulting, health care, manufacturing, financial services, nonprofit). The same measures of organizational virtuousness were obtained. Profitability (net income relative to total sales), quality, innovation, employee turnover, and customer retention were all measured as outcomes. Organizations scoring higher in virtuousness were significantly more profitable, and, when compared to competitors, industry averages, stated goals, and past performance, they also achieved significantly higher performance on other outcome measures.9

Another study exploring potential causal associations between virtuousness and performance was carried out in 29 nursing units in a large, comprehensive health care system. A multiyear study was conducted to investigate the effects of organizational virtuousness on indicators of performance. Multiday sessions were held with the nursing leaders and directors in this health system which exposed them to virtuous practices. On each performance indicator, units that improved in overall virtuousness outperformed units that did not in subsequent years. Virtuousness as viewed as a combination of individual virtues accounted for higher performance.10

Insights for Executives and HR Leaders

Executives are discovering that for them to lead better, they need to focus on living better. In this era of fast-paced change, rather than working harder, executives might consider slowing down and looking inward for opportunities to reinvent themselves. Employees throughout our organizations are hungry for leaders who are willing to change before they ask others to change. Modeling positive leadership changes will more likely inspire others to do likewise.

Leaders and employees who are mindful of the principles of positive change are then in a better position to help create a culture of virtuousness in organizations where integrity, compassion, creativity, honesty, and gratitude are accepted as “the way we do things around here.” If an organization has a culture that values honesty, fairness, and forgiveness, then the research shows that supervisors and subordinates are more likely to positively work through conflict. This in turn is not only positively associated with employee wellbeing, but also with organizational performance including higher productivity, quality outputs, profitability, productivity, customer retention, and lower employee turnover.

By making positive changes in their own lives, leaders are in a better position to engage in embedding virtuous practices into their company cultures which in turn becomes a strategic advantage for their organizations.

Brad Winn, Ph.D., is a senior editor for the People + Strategy journal and a leadership professor at Utah State University. He is an award-winning instructor who presents regularly at national events. He can be reached at brad.winn@usu.edu or see https://huntsman.usu.edu/directory/winn-bradley.

1 Sokol, M. (2018). Call for Papers. People + Strategy, 41.4.

2 Quinn, R.E. (1996). Deep Change: Discovering the Leader Within. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

3 Wexler, P.R. Literature Review & Self Analysis in the Context of “Deep Change.” Retrieved from http://www.moityca.com. br/pdfs/Deep%20change.pdf

4 Quinn, R.E. (1996). Deep Change: Discovering the Leader Within. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

5 Severson, E. (April 23, 2018). Personal interview at the HRPS Annual Conference. Scottdale, AZ.

6 Peterson, C. & Seligman M. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Oxford University Press.

7 Bright, D., Winn, B. & Kanov, J. (2014). Reconsidering Virtue: Differences of Perspective in Virtue Ethics and the Positive Social Sciences. Journal of Business Ethics, 119 (4)

8 Cameron, K. & Winn, B (2012). Virtuousness in Organizations. Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship. Oxford University Press.

9 Cameron, K., Bright, D. & Caza A. (2004). Exploring relationships between organizational virtuousness and performance. American Behavioral Scientist, 4, 766-790.

10 Cameron, K., Mora, C., Leutscher, T. & Calarco, M. (2011). Effectes of positive practices on organizational effectiveness. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47, 1-43.